Introduction

Lately, I’ve been distributing a lot of Slippery elm powder to folk in Los Angeles due to the fires and the pollutants they release into the air. It is a tree I know well from spending time with my friend Paul Strauss at his farm, Equinox Botanicals, in southern Ohio.

I hope you find this information interesting and useful. ~7Song

collection. If you are ever in the area (near Boston, Massachusetts),

I suggest visiting this museum. The detail is remarkable.

Botany

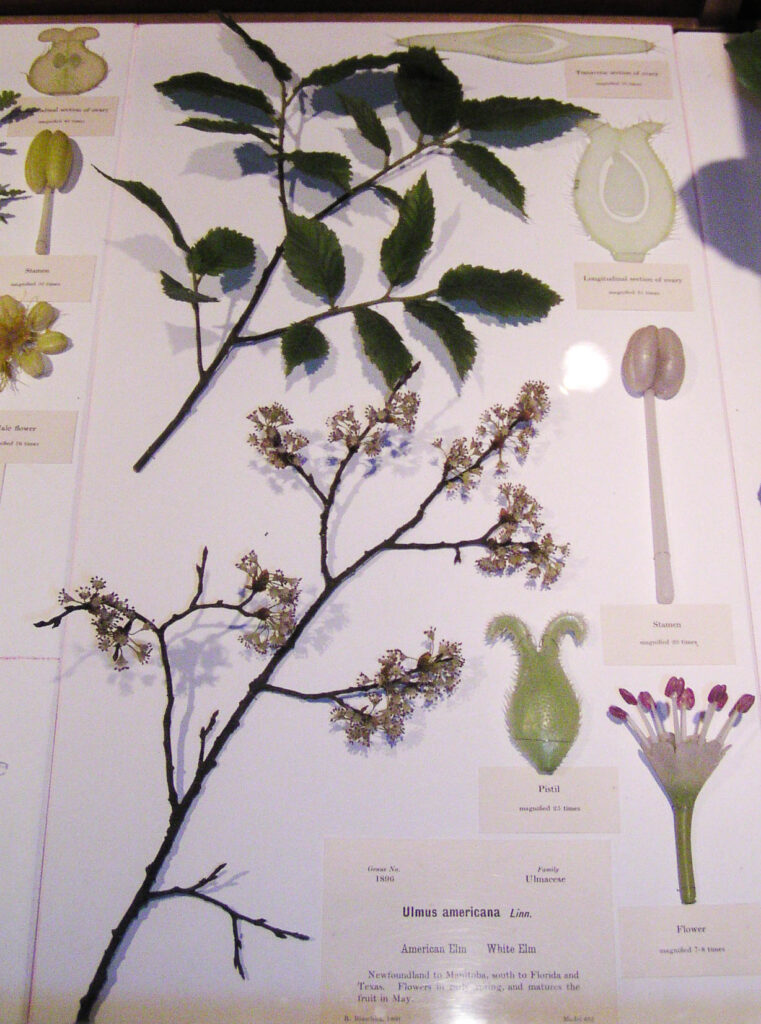

Slippery elm’s botanical name is Ulmus rubra. It is in the Ulmaceae (Elm family). Ulmus is an old name for Elms, and rubra means red. Red elm is another common name for this tree due to the color of the heartwood (see photo).

It is closely related to American elm (Ulmus americana), and like American elm, it is susceptible to Dutch elm disease (see Plant Notes).

(Ulmus americana) background. I was glad to get this photo

showing these two closely related trees next to each other

on Paul Strauss’s land in southern Ohio.

Medicinal Notes

The mucilaginous inner bark of Slippery elm is its primary medicinal constituent. This gives it its demulcent properties. The mucilage is made up of polysaccharides, a type of carbohydrate. These molecules absorb water and form a slimy (slippery) mass. It does not sound so appealing, but it can be soothing to the mucus membranes.

Slippery elm stands out among other demulcent plants for its profusion of mucilage and its lack of any poisonous or bitter elements, thus making it very safe to be useful internally and externally.

The main action of demulcents is to soothe the mucous membranes, which line all internal tissues that interact with the outside world. They include the gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and urinary tract.

While the mucilage only comes into physical contact with the GI tract, other mucus membranes are also affected and may start secreting mucus. How this action occurs is not understood, though symptoms are often relieved.

This demulcent effect has several functions. It acts as an antiinflammatory by soothing the mucosa. It can act as an expectorant by helping loosen and expel older sticky phlegm. It can also help reduce coughing by reducing bronchial irritation.

Due to these aspects, it is beneficial for some of the conditions associated with smoke inhalation (see previous newsletter or blog about Smoke Inhalation and Herbal Medicine).

By moistening and soothing the GI tract, it can help with a number of digestive ailments, such as gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD), recovery from diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and general GI dryness.

It can also be soothing to the bladder and urethra during urinary tract infections and other conditions causing painful urination.

It is important to note that it does not cure these disorders but lessens their symptoms.

It can also be used externally. It acts as an emollient and is soothing and moistening to dry or damaged skin. It does not help kill bacteria, so antibacterial plants should be used when there is a potential for infection.

Slippery elm is also called Red elm. This tree was cut down

as it was infected with Dutch elm disease, but the inner bark

was still useful medicinally.

Safety

Slippery elm is a very safe herb with no known adverse effects. I suppose you could choke on it if you made it thick enough. Or perhaps if it spilled on the floor, one could slip on it and fall on their dog, who then starts to bark loudly, causing a neighbor to rush in and step on your hand. The mucilage is its principal medicinal constituent.

Once in a while, you will come across information that says that Slippery elm can cause miscarriage. There is some background to this idea, though it is misrepresented. Thin pieces of the Slippery elm bark have been used for cervical ripening. They are inserted into the cervix pre-labor, where it absorbs water and helps soften and dilate the cervix to help facilitate birth. A type of seaweed, Laminaria, is also used in this way.

of Slippery elm.

Plant Notes

Slippery elm trees are threatened by both overharvesting and disease. They are not on any endangered lists as they readily stump sprout, though older trees are becoming rarer. Products from these trees should only be purchased from reliable, sustainable sources.

Slippery elm can be grown from seeds or seedlings, though it takes about 10 years before the bark can be harvested. It is native to the Eastern and Central states. The furthest west I have seen them was in Oklahoma.

Two diseases affect Slippery elm. They are Dutch elm disease and Elm phloem necrosis (Elm yellows). Dutch elm disease takes a few years to spread throughout and kill the tree. The tree can be cut down after it contracts the disease, and the inner bark can be harvested for medicine.

I have done this with infected trees on Paul Strauss’s land in Southern Ohio. (See Stories.) Elm phloem necrosis alters the inner bark, and I am not sure if it produces a viable medicine after the tree is infected.

Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila) is non-native and was widely planted as a street tree in the US. It has become invasive in some regions (I see it most commonly in New Mexico and Colorado, though it is widespread). The inner bark tastes as mucilaginous as Slippery elm and should be used as a substitute. While it is easy to gather Siberian elm, it is difficult to reduce the inner bark to a powder that dissolves in water. It requires equipment such as a hammer mill. But tea can be made from the young twigs and inner bark.

You can see brown fragments of the outer bark, which were

removed before peeling the inner (pale) bark.

Additional Notes

Slippery elm trees are fairly easy to recognize when one acquires an eye for them. Their leaves are hairy and have straight, deep veins. The buds are brown and hairy.

At the 1997 American Herbalist Guild conferences in Cincinnati, Ohio, I went on a botanical walk with a local elder botanist who showed us the Slippery elm leaf slap test. I found it to be both fun and informative and have shown it to hundreds of people since. To take the ‘test,’ put a leaf in the palm of your hand and slap your hands hard together. About 80% of the time, the leaf will stick to your palm when you turn your hand upside down. This is due to the rough hairs on the leaf. I don’t know any other Elm to do this. I’ve seen students try sticking the leaves to their faces to make a ‘Green man’ mask. The leaves will stick but also make the skin itchy and uncomfortable. Give the slap test a try sometime. It is good for children of all ages.

Slippery elm trees have multiple other uses. The most obvious is as a nourishing gruel. It is gentle on the stomach and can be one of the first foods after a bout of diarrhea. The fibers are also very strong and can be used for cordage and jewelry.

Dosage and Administration

Slippery elm has a long history as a safe plant, so the dosage is more related to how much mucilage is acceptable. Some people are quite put off by goop and gloop.

The powder is usually the most helpful preparation for internal applications, as it makes the most gelatinous medicinal beverage.

For a medium thick drink, pour 1 teaspoon of powder into ½ cup (4 oz) of water. It has to be stirred vigorously to dissolve the powder into the liquid; otherwise, it will clump together.

For tea using the shredded (as opposed to powdered) bark, I suggest using a French press, as it can be difficult to strain. Approximately 0.4-0.5 oz of the bark to 1 quart water gives a slightly demulcent sweet tea. Let it sit for about 1 hour. One difficulty is that the plunger on the French press cannot press the bark all the way down, so some of the mucilage will still be trapped in the plant matter.

The tincture can be added into tincture formulas for its demulcent quality.

For capsules, take 2-4 a few times daily.

rough hairs and straight, deeply grooved veins.

Medicine Preparation Notes

I am still working on a better way to make this tincture. I am currently double macerating it by tincturing dried bark into a previous Slippery elm tincture. It is too early to know how it will turn out.

A hammer mill or similar equipment is needed to reduce the inner bark into a fine powder so that it will dissolve and make a gelatinous mass in water.

Stories

Most of my Slippery elm stories are from the many years I brought my class on field trips to Paul Strauss’s home in Southern Ohio starting around 1995. Back then, Paul had a number of large, stately Slippery elm trees growing in his woodlands. But over the years most got infected by Dutch elm disease. You could see the initial stages of the disease as the branches at the top of the tree started dying. Since the tree was going to succumb in a year or two, Paul would cut these trees down for us so we could harvest the inner bark, which was still mucilaginous. I was very appreciative for this opportunity, but sorry that the trees were dying.

Here is another Slippery elm story from Paul’s. He and I were taking a walk near his home, where he had a tree growing near the road with some of its roots exposed. Paul cut off a chunk of the root bark, which we both started to chew. And it was the gloopiest, most mucilaginous bark I have ever tasted. I think both of us had Slippery elm spittle as the moisture overwhelmed our mouths. It was delish.

that can be used as an alternative to Slippery elm.

in New York City. American elms were a widely planted street tree

in the US but were decimated by Dutch elm disease.

These trees were probably treated to kill the infection.

interesting-looking leaf skeleton behind.